“Mr. Conte … has casually dropped words like logomachy.”

—New York Times, Aug. 29, 2019

It seems that Italy’s Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte not only cuts una bella figura (we are told he wears purple ties), he is also something of an aureate orator: either golden-tongued or just affected, depending on your understanding of aureate. And if you engage in logomachy.

Presumably, for most Times readers, these gossipy snipes were a bit of extraneous color commentary wedged into the bigger story: Conte’s brilliant side-lining of Matteo Salvini. It is one of the few political successes in countering one of the all-too-many rabid nationalisms that would happily replace democracy with fascism.

As encouraging as that news is, the prose that delivered it is disheartening. There is an unmistakably pejorative undertone signaled with a wink and a nod by “purple” and “logomachy.” The former characterizes Conte as a dandy and the latter as pretentious. They have the effect of reinforcing a persistent stereotype of Italians as preoccupied with form at the expense of substance. Not to be taken seriously, at least in politics.

But it’s the implicit disparagement of “logomachy” that really sticks in my craw. Discovering a new word (and it was for me) is one of life’s small but delectable pleasures – and it’s free. More importantly, logomachy – literally, word-fight – is a popular democratic sport. When the meaning of words is dictated and not debated, there’s a good chance you’re living in a totalitarian state.

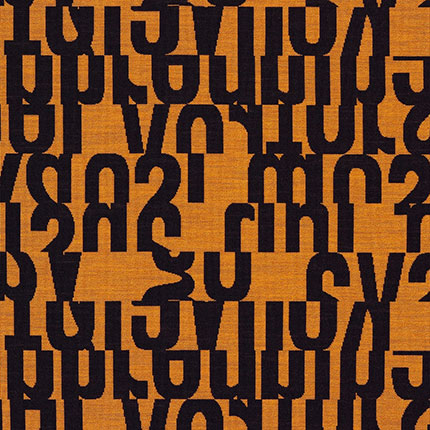

Logomachy asks that we “step in between the words.”(1) That we turn them around and see them from different perspectives.(2) Like letterforms, words have bodies and sensory properties. The hard “g” and “ch” give logomachy its combative tone. Happily, that’s muted by the awkward marriage of its parts: “logo” is definitive, “machy” seems messy. Like democracy. Always an act of faith, no more so in Italy than here at home.

1. Olga Tokarczuk, Flights. (New York: Penguin, 2018) 73.

2. And clearly not the inverted Orwellian logic of nomenclatures like the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. I’m thinking of words here from a phenomenological perspective.

3. My bifurcation of ‘logo’ and ‘macho’ isn’t a guide to the word’s pronunciation, which is lo-gamachy. Emphasis on ‘lo.’