As design practices become more nuanced to increase their relevance and efficacy, the word ‘design’ is at risk of losing its meaning. Likewise, the value of design, already confused with lifestyle attributes, is also being obscured. The traditional fields of graphic design, product design, fashion, interiors, architecture, and urbanism have now been amplified by communication design, technology design, strategic design and management, service design, social design, transition design, design studies, design anthropology, design research, and design philosophy. With the best of intentions, design has become simultaneously splintered and bloated.

This would seem to be an insider’s problem. Surely no one outside of the design community sees their digital devices, the streets they walk on, their social networks, and their homes in terms of the types of practices that inform them. Though I suspect some people might find it interesting to learn that these things grow out of much the same motivations that govern their own responses to the world—namely, to control, to convince, to come together, and to rebel.

That said, I believe that the designers and those who think about design might profit from seeing how those four elementary responses to the events of daily life inform the outcomes of design. By examining how design’s ambitions are made manifest in objects, buildings, landscapes, systems, and cities across time, we can see design’s reciprocity with ambitions that govern human behavior more broadly. There is the ambition to make things uni-form, the ambition to make them per-form, to co-form and to de-form. These categories, understood as constant through time though variable in their manifestations, allow us to think of design as behavioral and cyclical. It offers a more relevant view of design’s efficacy—one that is not estranged from the present but one that is fundamentally familiar. The taxonomy of these four notions of form and forming is the opposite of a linear history that begins with, say, the Greeks and comes up to the present, chipping off parts of the past as it goes, deeming them irrelevant to our lives today. Instead it offers formations that are part of a living trajectory while respecting the different ways those ambitions seek and find form.

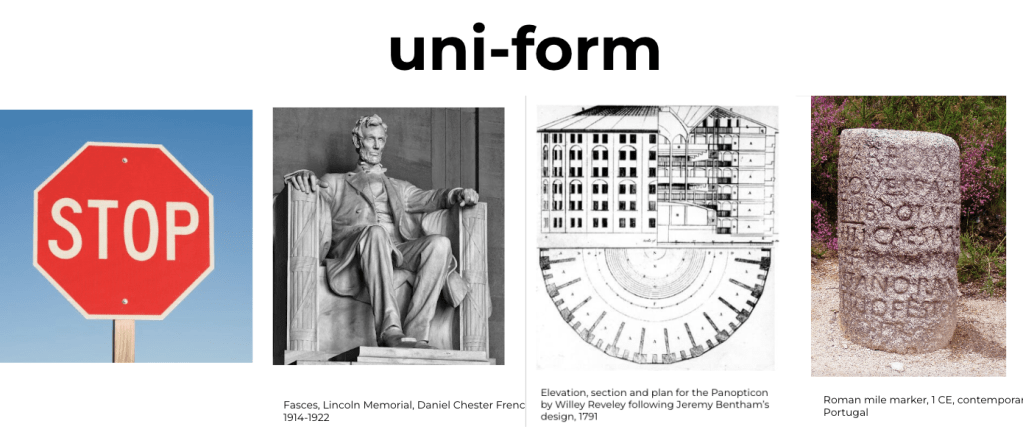

Of the four, the desire to make things uni-form may be the oldest, as it is about control, and is rooted in keeping us safe from threats. However, it may also be the most pernicious when its emphasis on authority tips over to tyranny.

To per-form is to make space for movement and organic growth. Performance operates on the principles of seduction and persuasion.

Co-forming is a matter of sharing control and rejecting a single author; co-forming is often thought of as democratically social, but it can also be understood as a process of meshing materials, as in weaving.

De-forming is resistance to control, with which it has a symbiotic relationship. It operates in registers ranging from the humorous to the anxious to the rebellious.

Note the use of hyphens in each of the categories of ambition. It is a deliberate nod to design’s essential work of giving form to ideas about our relationships with each other and other sentient and insentient beings—relationships that are negotiated through and by things. Things being inclusive of tangible objects like the common stop sign as well as intangible structures like health care systems. Furthermore, the conceit of using ‘form’ as the second syllable of every ambition alludes to fact that they share in the praxis of shaping matter and matters. In doing so—since no one category of ambition has sole claim to a specific type of form or forming—they also yield hybrid ambitions that work on the principle of dominant and recessive genes. (For example, Antoni Gaudi’s Basilica de Sagrada Familia in Barcelona per-forms a spatial seduction through its iconoclastic ornamentation and winding, sinuous spaces, while secondarily de-forming ecclesiastical conventions.)

Interior, Sagrada Familia, Antoni Gaudi, 1882-2026

Identifying the character and essence of design ambitions across the centuries, reveals common threads among us as a fallible but hopeful designing species. Here are some examples:

The project now is to amplify the western bias visible in most of the images above. Questions arise in my mind such as:

Would other cultures find the four ‘ambitions’ pertinent in describing their design dynamics? What values might be missing? How to contend with ritual objects which are integral to performance but are co-formed, such as the ideographs of the Nsibidi in southeastern Nigeria. These patterns are used in secret rites as well as in celebrations; they are printed on textiles and tatooed on bodies. The makers are not privy to the meaning of the symbols but they are essential to their production. If I were to place this cloth within my rubric, I would say it is co-formed in service of the per-formance of rituals. However, use, process, and iconography are so very closely related that I wonder if my metaphor of dominant (co-form) and recessive (per-form) genes still holds.

Nsibidi on the Igbo ‘Ukara’ cloth of the Ekpe society

The same questions hold true for a host of other works of design. But I will just mention two more, as my own ‘ambition’ is not to be encyclopedic but rather to find markers to make sense of design beyond the formally sanctioned cultural/historical categories–without denying that terms like classicism, baroque, or vernacular do have their uses.

Take the Hawa Mahal in Jaipur which was designed by Lal Chand Ustad in 1799. Its curvaceous east facade both meanders horizontally and grows vertically. This palace fuses Hindu and Islamic motifs which can be seen respectively in its domed canopies, fluted pillars, lotus, and floral patterns; and its inlay filigree work and arches. Both because it is a seat of power, and because of its tautly controlled decoration, I’m inclined to think its dominant gene is uniformity and its recessive, performity. But is that true to the essence of the Jaipur palace?

East facade of Hawa Mahal, Jaipur, Rajasthan, Lal Chand Ustad, 1799

My last example is from China, the timber pagoda of the Fogong Temple from 1056, Song dynasty; at Yingxian, Shanxi province. My western eyes see only verticality, symmetry, and uniformity. But further reading reveals that the ‘tower’ form derives from that of the Buddhist stupa, a hemispherical, domed, commemorative monument first constructed in ancient India. Could that affect the value(s) it signifies?

Timber pagoda of the Fogong Temple, 1056, Song dynasty; at Yingxian, Shanxi province, China.

These are just some of the questions that will drive the next phase of my research. Thoughts and suggestions are more than welcome as I continue to search for sources that will amplify my understanding of design and its values.